I think that competition can be very healthy, but I think also that the desire to compete can have its roots in both unhealthy and healthy ideas. One of the challenges that we face as athletes, as coaches, as teachers is ferreting out how we (or our clients) feel about competition, and helping them to see that competition is nothing but an opportunity to turn failure into success. And I say this because any action we do can be improved, regardless of how we place in a competition.

When my husband was young, he joined the cross-country team at his high school. He had never run before, but he was lean, wiry and fast from playing soccer for years. His new team ran around the track for two days, and then went on a four-mile run. Tom was the slowest, having never run a distance like that before. When he got back, he was exhausted, and frustrated. The coach praised those who were fast and had finished first, and did not tell young Tom that with time, practice and technique, he would improve. He did not find anything in what Tom had done that was a success, no matter how small, leaving Tom to feel that he was not talented at this sport, and could never be a success at it. His failure was paramount. His failure defined his future in the sport. Over the course of his life, this singular experience informed the way he felt about himself, how he defined himself.

I think about this when I think about teaching skiing. The power of a coach or a teacher is immense, as is the responsibility. You have in that moment, the chance to change a person’s life forever. To help them redefine themselves, to believe in themselves in a way that they possibly never have before.

When I coach any of the sports that I teach in, I think about this as my first priority. Help the client to see himself or herself in a new light. And more importantly, turn their failures into a tool they can use to make new breakthroughs in their sport.

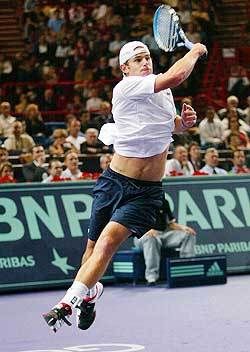

But look at the rest of his game. He is most likely working around every ball, trying to turn each ball into his favorite, point-winning shot. He will run around his backhand and hit a bad forehand. He will, if you are patient, beat himself.

Now this guy, with this unbeatable down the line shot and no other tools in his arsenal can look at a match in two ways. It is a game to be won with his fearsome weapon that he has honed over time, or it is an opportunity to test where he is so he can develop a complete game and be a better player over all.

I want to think for a moment about the coach’s ability to infuse the client with a NEW sense of purpose in competition, regardless of their early life experience.

Lets say that we managed to get our hands on Mr. Down The Line. What if we could spend a day with him, and watch him lose his match to an average player with an assortment of average shots and no winning weapon. Mr. Down the Line is down on himself. He has failed. He trained hard, and did not win. His feeling is one of loss, diminished sense of self, and sadness. He probably will go work out the next day and hone that fearsome weapon into something even faster, even closer to the net, even more backspin on it, until it seems unbeatable.

In this way, using “failure” as a diagnostic tool, a client can see that perhaps they can leave their Forehand Down the Line shot for a few weeks, and concentrate instead on the skills that are lacking. I always tell my clients, lets find the thing that you are the WORST at. And then let’s drill it until it is your strength. In this way, you have a list of skills you are constantly eliminating as impediments to success, and turning them into strengths.

Imagine the feeling this client could have suddenly looking at competition as a way to determine his weaknesses, training for three weeks to remove them or turn them into strengths, and looking forward to the next competition to see if he had trained them hard enough, if he needs more work on them, or if he has a new weakness that needs work. Eventually, he will be a total athlete, well rounded, with a toolbag full of skills, some always better than others, PLUS his wicked down the line shot.

If we could get this guy to change his attitude toward competition to view it, and any “failures” within it as diagnostic tools, and to be excited to uncover new weaknesses and change them instead into strengths, over time he will learn to love competition because it is a tool that helps him truly excel at the sport that he loves. You have done this guy a big favor. He doesn’t compete to win anymore, winning is a byproduct of using competition and training wisely. He doesn’t strive for self worth through his medal collection, his worth is defined internally now through his new work ethic, or (even better) his worth is no longer tied to his performance in sports, leaving him emotionally free to try hard, the fear of failure is gone, because failure is something he loves now. Failure is the pointer that shows him what he gets to work on next.

Oh, this is exciting! How formidable would I be as a competitor, how much of a fantastic teacher will I be if I can conquer frozen coral reef? Good lord, can you imagine being able to Josh Foster your way down the steepest, gnarliest, least forgiving frozen fingers of death? Lets make THAT a strength!

How do we do that? Read everything we can get our hands on about skiing in icy conditions (Oh, MAN am I excited about the movement Matrix for this reason!), watch video of people doing it. Try it on frozen groomers. Graduate to frozen crud, that’s not so steep. Get up early before the sun warms it up in the spring and put in the time on the worst stuff you can find. Get frustrated. Reward yourself for skiing in stuff you hate, for challenging yourself to try anyway, by skiing something easy and ego boosting after the sun comes out. Just one or two quickies that make you feel like the king of the world (This would be 10 minutes of practicing that down the line shot in a 90 minute workout). Keep doing it until you suck less.

Then do it until you own it. Then test yourself and realize that you now suck at powder skiing, tree skiing, chutes, steeps, bootpacking, whatever, and make it your strength.

Failure is an athlete’s greatest ally. The way we measure where we are and what skills we need to move forward in our sport without fear. In turning failure from a self-defining, worth breaking harridan into our favorite best friend, we free ourselves from fear of failure. Imagine what you could try if you were not only not AFRAID of failure, but excited about it? And then, imagine the scope of your possibilities for success.

No comments:

Post a Comment